Software Threads VS Hardware Threads

Recently, I’ve been reading the Dinosaur Book to learn about the fundamentals of an operating system. As I went through the CPU scheduling chapter, I stumbled upon hardware threads.

If you took an introductory course on computer science, you might have learned about threads and concurrency. The threads used in this context are the software threads. One of the most common implementation of threads in software is a server where the process could have a pool of threads listening (waiting) for a request (connection) to occur from a client. By utilizing threads through a library such as pthreads, one can create a responsive and efficient program.

In contrary to software threads, the hardware threads are the ones in the CPU. Nowadays, technology has improved to the point where not only is there multicore CPUs, but also multi-threaded/hyper-threaded cores. So, you might see products like AMD’s Threadripper CPU with 64 cores and 128 threads.

Before reading this book, I was always curious about the relation between these two types of threads and the introduction of hardware threads answered my long-lasting curiosity. I wanted to create this post to leave a record not only for myself but also for others with the same query. A lot of the information is based on the book, so if you find any mistakes, please let me know :)

To begin with, let’s see how hardware threads can benefit the system. When a CPU executes instructions passed onto it, some instructions might make the CPU read from the memory and perhaps store it in the CPU register for later use. Turns out, this simple task of reading a value from memory isn’t really that quick compared to the execution speed of the CPU. This situation is known as a memory stall where the CPU is bottle necked by the procedure of accessing the memory. Even if the speed of accessing memory was on par with the execution speed of the CPU, memory stall can still occur due to cache miss.

The image above shows the hierarchy of memory. The higher it is in the hierarchy, it is much faster to access, but the capacity is limited and expensive. Therefore, an L1 cache is faster than the main memory (RAM), but the amount of data it can store is significantly around few KiB (or MiB). Since the cache is too small compared to main memory, it cannot hold all the memory stacks of all the running processes. Therefore, occasionally, the computer will have to look for the data that is not found in the caches. This situation is described as a cache miss.

Might have gone a little deep in the rabbit hole, but to sum it up, CPU is blocked while waiting for the memory fetch. This is not good as the CPU stays idle when it could be executing some other instructions. So, to reduce memory stall, an additional thread could be feeding in instructions to the CPU instead.

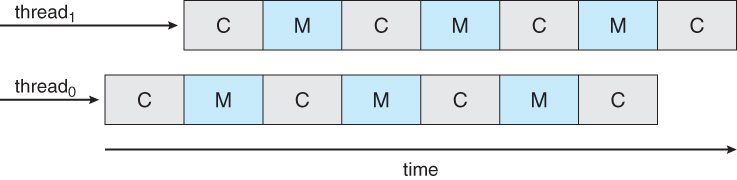

The above image is from the book where C indicates compute cycle and M indicates memory stall cycle. By utilizing two threads on one CPU core, an idealistic situation like above would remove memory stall.

Now that the purpose of hardware threads are clear, let’s see how the hardware threads interact with the software threads.

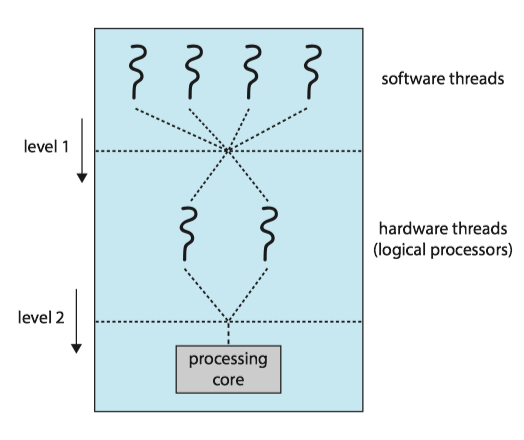

The image above shows many software threads being assigned to the hardware threads and also hardware threads assigned to the processing core. The latter has already been discussed above (except for how it is scheduled). The former is managed by the operating system. Commonly, the operating system interprets the hardware threads as individual CPUs (logical CPUs) and schedules the software threads to the hardware threads using algorithms such as round-robin, priority queue, and more complex algorithms. In some cases, the operating system might recognize the hardware threads (distinct from logical CPUs) and actually assign software threads on a completely different core rather than a hardware thread to actually benefit the multi-core processor.

Long story short, in summary, the operating system schedules software threads on hardware threads to execute the instructions.