Delta Over-The-Air Device Firmware Update

Like receiving updates for your mobile application or upgrading your favorite text editor to the latest version, embedded devices may also need to update their firmware from time to time. The reason could be to receive a new feature, patch a vulnerability within the current firmware, and more. However, unlike the more powerful devices such as your ordinary desktops with multiple CPU cores and gigabytes of memory, microcontrollers commonly used in embedded systems are quite limited, oftentimes single-core with few kilobytes of memory. So, in order to receive updates in a timely manner, it needs to be efficient with the constrained resources while performing as expected.

A method that is shown in this project is the delta over-the-air update, where only the differential of the old firmware image (binary executable) and the new firmware image is sent instead of sending the entire new image. In the sample test cases explained later, this results in a significant reduction (4.71% on average) of data being transferred. Furthermore, although it requires more testing of various sorts, I think that the reduction in I/O has resulted in faster updates.

Implementation

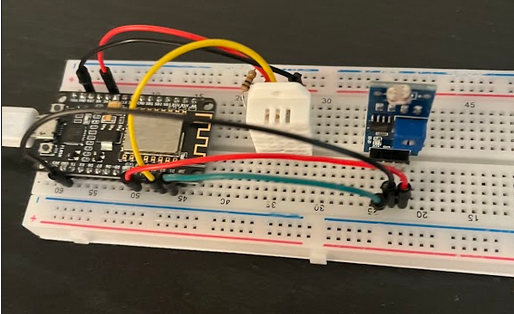

The ESP8266 (NodeMCU) microcontroller and the ESP8266 Real-Time Operating System SDK (based on FreeRTOS) have been used for this project. In order to simulate a realistic load on the device, I’ve included I/O operations with external sensors (temperature, humidity, light, and LED) through the GPIO pins on the board.

For handling the update process using the delta OTA update method, Heatshrink—to decompress the delta file—and Detools—to generate the delta file and apply the update at the device—were used.

At first, I wanted to use bsdiff to generate/apply the delta file. However, I’ve soon realized that the original implementation of bsdiff was not suitable for embedded systems due to its dynamic memory allocation. So, I went with Heatshrink and Detools as it was made for resource-constrained environments with a compression algorithm suited for small files that use static memory.

Since the purpose of this project is to focus on the delta OTA update functionality, I’ve implemented a rudimentary pub/sub messaging broker based on TCP with some basic application protocols to let the devices subscribe to the appropriate update topics and publish data. A demo of the full delta OTA update process is shown below.

Update Process Flow

As shown in the demo video, the general flow of the update process goes as follows: First, the device boots and subscribes to a certain topic that will be used later on to send and receive updates. Then, the delta file is generated and uploaded to the hub by another host. The hub relays the file to the subscribed devices that responded to the heartbeat messages. Heartbeat messages are used to close any dead connections. Once the device starts receiving the delta file, it stores it in storage to decompress it and apply the update.

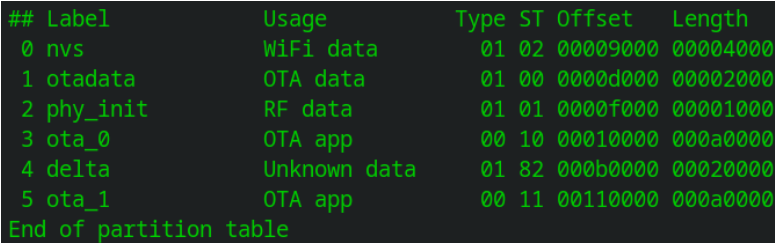

The device storage is partitioned into an A/B partition, where one partition contains the code that is currently running and the other stores the new firmware image to boot from. When the update has been successfully applied to the next partition, the device will go through a software reset and boot using the partition that contains the new firmware image.

Comparing DOTA to OTA

Various scenarios have been implemented to compare between the normal OTA update method (full image) and the delta OTA update method (delta). The individual test results can be seen here. Despite the variety of test cases, the size of the images didn’t show much difference (at maximum 5 KB difference), as most of the space in the image was related to the tcp/ip library, which accounted for more than 300 KB. I think this can potentially render the results of the comparison meaningless.

Regardless, in the normal update method, it took 17.89 seconds on average in 35 tests and 5 scenarios. In the delta OTA update method, it took 15.25 seconds on average in the same test cases. So, the delta OTA update was 2.64 seconds faster overall, but there were quite a number of outliers in the test results. With almost 15% of the test cases being classified as outliers by the 1.5 IQR rule, I think the outliers were related to process scheduling, as they disappeared as soon as the scheduling of the OTA update tasks was altered by the introduction of long polling I/O. However, this is just speculation, as I was not successful in properly debugging the process.

Conclusion

Although delta OTA is nothing new, I think this project was a good introduction to embedded development as it was mostly focused on software while having resource restrictions (encountering stack canaries from time to time). I was able to start off with a popular embedded development platform (Platform IO), although I had to move on to the ESP8266 development environment as there were some issues with Platform IO being a bit outdated. I also had the opportunity to include a fair amount of GPIO programming into the project outside of the Arduino platform. In the process of implementing the simple pub/sub messaging broker, I was able to learn more about multithreaded programming with synchronization of the interface and network tasks through semaphores. Mostly for debugging, I also had the chance to use Wireshark to analyze traffic using filters outside of class, which was very useful for figuring out why data between the ESP8266 device and the broker was being dropped (the culprit was the firewall).

In the following projects, I hope to get more experience with the real-time aspect of embedded systems and get my hands dirty with hardware by implementing device drivers. Also, I think it would be great to get familiar with commercial IoT or embedded systems-related services and platforms such as AWS IoT, Kafka, and Yocto.